Location of the Tortugas shipwreck off the Dry Tortugas islands, Florida Keys. (Unless otherwise noted, all photos © Odyssey Marine Exploration.)

The research vessel Seahawk Retriever in port before sailing to the Tortugas shipwreck. (Photo, John Astley.)

The remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Merlin, the eyes and hands of the archaeologist on the deep-sea Tortugas wreck excavation, docked on the deck of the Seahawk Retriever. (Photo, John Astley.)

Recovered artifacts from the Tortugas shipwreck on the deck of the Seahawk Retriever. (Photo, John Astley.)

Large Type 1 and small Type 2 olive jars (botijas) from the Tortugas shipwreck. Large Type 1: H. 17 1/8–22 1/4"; small Type 2: H. 10 5/8–13 3/8".

Olive jars and a San Juan Polychrome juglet in situ on the wreck.

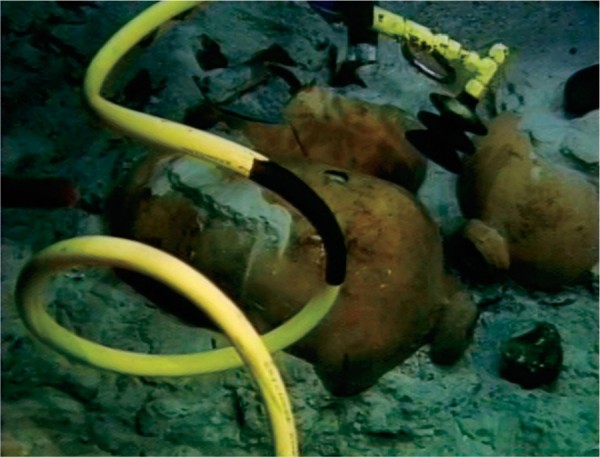

A Type 1 olive jar being recovered using a limpet suction device.

A Type 2 olive jar being recovered using a limpet suction device.

A Type 3 olive jar in situ.

Olive jar sherds alongside a half-dipped juglet in situ.

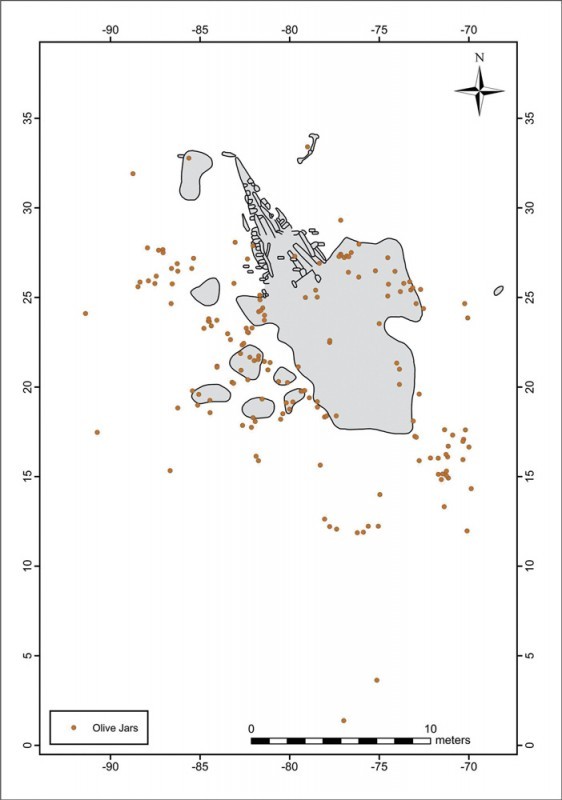

Map showing the distribution of olive jars at the 400 meter-deep Tortugas shipwreck.

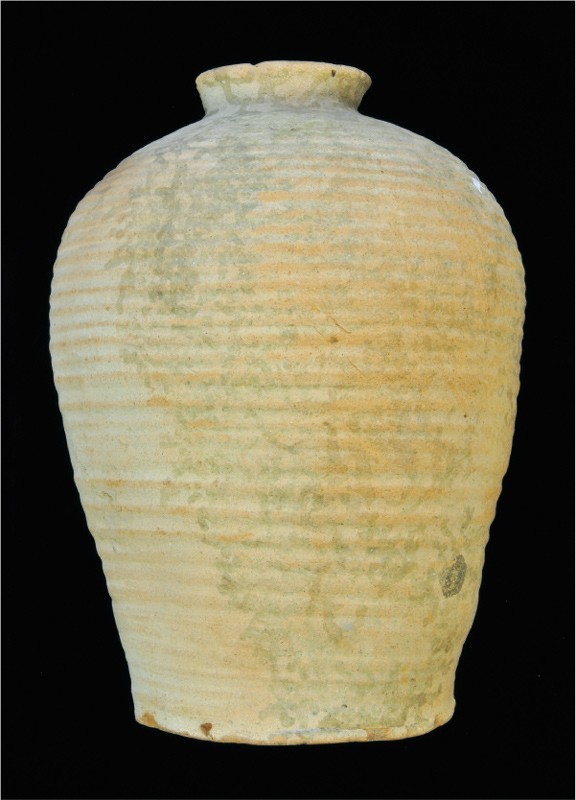

Tortugas Type 1 olive jar, possibly Córdoba, Spain, ca. 1622. Unglazed earthenware. H. 21 1/16".

Tortugas Type 2 olive jar, Seville, Spain, ca. 1622. Unglazed earthenware. H. 12 3/16".

Tortugas Type 4 olive jar, Seville, Spain, ca. 1622. Unglazed earthenware. H. 16 11/16".

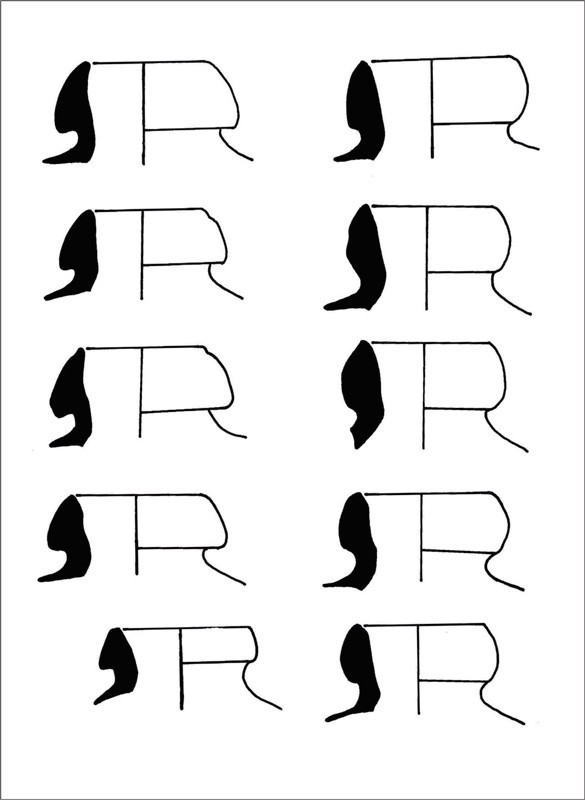

Tortugas olive jar rims: (left) Type 1; (right) Type 2. (As illustrated in George Avery, “Pots as Packaging: The Spanish Olive Jar and Andalusian Transatlantic Commercial Activity, 16th–18th Centuries,” Ph.D. diss., University of Florida, 1997, p. 115.)

Sample sgraffito maker’s marks incised onto Tortugas olive jar rims.

Plate and dish fragments, Blue-on-Blue Seville maiolica, Seville, Spain, ca. 1622. Tin-glazed earthenware.

Dish fragments, Blue-on-White Talavera–style maiolica, Seville, Spain, ca. 1622. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. of largest fragment (center) 7 13/16".

Dishes, Columbia Plain maiolica, Rio Guardiamar, Andalusia, Spain, ca. 1622. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. of largest dish 7 13/16".

Tin-glazed vessels recovered from the Tortugas shipwreck, ca. 1622. (Top row) Juglets, Andalusia Polychrome maiolica, Andalusia region, Spain. H. of largest juglet (top right) 3 13/16", D. 3 7/8". (Bottom row) Bowls, Seville, Spain. H. of Seville white ware dish (bottom left) 2 5/16", D. 5 5/8".

(Top row) Linear Blue Morisco ware jugs, ca. 1622. Tin-enameled earthenware. (Bottom row, left to right) Mottled Blue Morisco ware cup from the “high magnesium” subgroup; Blue-on-White Seville ware bowl; and juglet from the “high magnesium” subgroup.

Red earthenware vessels recovered from the Tortugas shipwreck, ca. 1622. Left to right: Half-dipped green glaze juglet from the high magnesium subgroup; one-handle Portuguese redware jug; a green-glazed coarse redware jug; and a coarse ware glazed juglet. H. of one-handled Portuguese jug (second from left) 11 7/16".

Fragments of colonoware cooking vessels, Southern Atlantic/Circum-Caribbean, ca. 1622. Low-fired earthenware.

The Florida Keys are an unforgiving graveyard where the backs of a thousand hulls, shattered by relentless hurricanes, are consigned to the deep. The Spanish Tierra Firme fleet returning from Havana to Seville in early September 1622 is the most famous casualty, where the loss of 1.28 million pesos on the Nuestra Señora de Atocha and Santa Margarita sent shock waves across the Atlantic to debt-ridden Madrid. These treasure ships symbolize both Spain’s dependence on the Americas and the beginning of the end of the Golden Age of Spain and its commercial dominance over the New World.

In 1989 Seahawk Deep Ocean Technology of Tampa, Florida, discovered a colonial-era shipwreck at a depth of four hundred meters off the Dry Tortugas islands in the Florida Keys (fig. 1). The following year a unique archaeological project began under the direction of Odyssey Marine Exploration’s CEO Greg Stemm and its co-founder John Morris. Throughout 1990 and 1991 the site’s entire archaeological assemblages were recorded and recovered, exclusively using pioneering robotic technology developed around a wizardly remotely operated vehicle (ROV) called “Merlin”. The project was the world’s first robotic shipwreck excavation (figs. 2-4).

The Tortugas wreck’s 16,903 artifacts—from olive jars to domestic pottery, silver coins, gold bars, astrolabes, pearls, beads, and glassware—so closely match by date and type the assemblages associated with the Atocha and Margarita that this ship indisputably sailed with the ill-fated Tierra Firme fleet lost on September 5, 1622. Unlike the more celebrated wrecks whose remains are scattered under deep sand blankets across enormous swaths of the Florida Keys, the Tortugas wreck had a coherent site formation. Odyssey Marine Exploration, the collection owner, is currently preparing the final publication of the site.

Although elements of the upper stratum of the well-preserved hull were recorded, notably the stern and pump well, of greatest evidential value are the extensive artifact assemblages. In volume and variety these are unparalleled among other sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Spanish shipwrecks worldwide (figs. 5-10). They provide an opportunity to assess the cultural tastes of Iberian sailors on the Americas trade route, as well as the control of Seville and the Casa de la Contratación (House of Trade) over fleet supply.

Unlike the great galleon Atocha, whose ceramic repertoire has been well characterized, the Tortugas ship comes from the opposite end of the social spectrum.[1] The remains most closely match the El Buen Jesús y Nuestra Señora del Rosario, a small Portuguese-built and Spanish-operated navio of 117 tons and 37 codos length (21.3 meters, or approximately 70 feet) owned by Juan de la Torre Ayala, captained by Manuel Diaz, and outward bound for Nueva Cordoba on the Pearl Coast in eastern Venezuela. What ceramic styles did this ship’s crew prefer? How cosmopolitan were their tastes and how do they reflect contemporary socioeconomic currents? The policy of total ceramic recovery pursued during the wreck’s excavation has permitted a qualitative approach to address these questions. As part of the post-excavation research, in 2011 Dr. Michael Hughes undertook inductively coupled plasma spectrometry (ICPS) of sample clay fabrics from the Tortugas wreck to chemically fingerprint the pottery’s sources.

The Botijas (Olive Jars)

The most conspicuous material culture on the Tortugas shipwreck’s surface consisted of 86 intact olive jars and 123 individual rims (alongside several thousand fragments). The ship was thus transporting at least 209 olive jars in four types that were relatively evenly distributed around the central ballast mound (fig. 11).

Accounting for 87.2 percent of the total botija assemblage is a form de-fined as “Tortugas Type 1,” comparable to John Goggin’s Middle Style A.[2] This type is characterized by a classic tall body and a rounded shoulder surmounted by a low rim inclining relatively smoothly to a gently rounded base (fig. 12). Heights of these vessels range between 17 1/8 and 22 1/4 inches. The maximum diameters range between 7 and 13 3/8 inches, the rim heights between 13/16 and 1 3/4 of an inch. Volumes range between 14.2 and 22.5 liters.

Tortugas Type 2, which makes up 8.1 percent of the total, is comparable to Goggin’s Middle Style B—a small, compact globular jar, almost circular in anatomy, with a continuously rounded base, body, and shoulder (fig. 13). These vary in height from 10 5/8 and 13 3/8 inches, with maximum diameters from 9 3/8 to 10 1/8 inches. The heights of the rim range between 1 and 1 9/16 of an inch. Volumes range between 3.7 and 8.1 liters.

Tortugas Type 3 represents 2.3 percent of the assemblage and is comparable to Goggin’s Middle Style C, which is a carrot-shaped vessel, far narrower than the above series, with a slender body, more V-shaped in profile and leading to a more pointed toe (see fig. 9). The simply rounded rim surmounting a short neck equates to half the jar’s width, far wider than the diameter of the vessel necks in Tortugas Types 1 and 2. The height of this jar is 13 inches, the diameter is 6 1/4 inches, and the volume is 2.8 liters.

Tortugas Type 4, which also accounts for 2.3 percent of the total assemblage, features a neck and body shape that is anatomically similar to Tortugas Type 1 but is differentiated by an everted neck, a short, slender rim, a vertical profile along the lower third of the vessel and, notably, a flat base (fig. 14). The height of this vessel is 17 1/8 inches and the maximum diameter is 12 1/4 inches; the diameter of the mouth is 4 5/8 inches. The volume is 20.8 liters. In function Type 4 vessels are better suited for use as kitchenware than as transport jars.

The botijas range in color between very pale brown (10YR 7/3 on the Munsell Color System), reddish yellow (5YR 6/6), and light red (7.5YR 6/6). Traces of green glaze, common on olive jars from terrestrial sites, occur across the exterior of only a few sherds.

In terms of rim profiles, Type 1 examples are angular and Type 2 shapes are rounded (fig. 15).[3] The traditional Type 1 rim displays a wide overhang above the neck; the Type 2 globular jar rim is narrower and has less overhang. On average, the interior throat diameter of Type 1 jar rims is 1 7/8 inches and the maximum rim diameter is 3 11/16 inches. The average Type 2 rim diameter is 1 7/8 inches for the interior throat and 3 3/8 inches maximum.

Crude sgraffito on the shoulder and rims of a minority of olive jars appears for the most part to have been incised prior to firing (fig. 16). Examples include a Jerusalem cross (perhaps indicative of production on an ecclesiastical estate), an unidentifiable pecked design, and hollow circles similar to production marks found on jars recovered from the wreck of the San Martin of 1618, the Santo Domingo Monastery at La Antigua in Guatemala, and the colonial port of Bodegas in northeast Guatemala.

During the ship’s descent to the sea bottom, or soon after deposition, the pressure exerted on the olive jars forced their cork seals to implode: intact and fragmentary corks were found preserved inside some vessels. Intact examples were tapered and measured 2–2 3/8 inches on the upper plane, 1 7/8–2 inches on the lower plane, and 9/16–15/16 inches thick.[4]

Despite the catch-all misnomer “olive jars,” it seems that Spanish merchants did not differentiate jars by shape or by content but by size, from the botija de cuarto de arroba of 2.87 liters to the botija de arroba y media of 16.5 liters.[5] Although no jar contents survived intact on the Tortugas wreck, a pioneering sieve filter system built onto the back of the ROV recovered 565 intact seeds, including almond, plum, peach, grape, hazelnut, olive, peach, cherry, and squash. The seeds are likely to reflect some of the original contents of the jars.

The 209 botijas are a relatively small consignment volume and are best interpreted as ship’s stores, used by the crew and passengers on the return voyage to Spain rather than as cargo.[6] By contrast, the outward-bound manifest for El Buen Jesús y Nuestra Señora del Rosario (Contratación 1172, N.2, R.1) specifies that at Seville private merchants were to consign as cargo at least 1,400 jars containing wine from Aljarafe, Trebujena (Seville), Salteras (Seville), and Sierras Llanas, most for delivery to Nueva Córdoba in eastern Venezuela and lesser amounts for Rió de la Hacha in modern Colombia. Also listed as outward-bound were raisins, hazelnuts, almonds, chestnuts, oil, capers, olives, brandy, and sherry, some of which almost certainly would have been packaged in botijas too.

Maiolica Tablewares

Of greatest significance within the Tortugas artifact collection is the assemblage of 2,304 kitchen and tableware rims, handles, bases, and sherds (1,390 tin-glazed maiolica and 84 blue-painted tablewares, 279 colonoware kitchen vessels, 218 unglazed coarse redwares, and 333 glazed coarse redwares), representing twenty-two types of pottery forms.

A limited range of four types of maiolica dishes (platos) and bowls (escudillas) were recovered, which accounts for nearly three-quarters of all of the tablewares:

Blue-on-Blue Seville 48.4%

Blue-on-White Talavera 13.5%

White Seville 6.0%

Columbia Plain 6.5%

Counts of predominantly intact vessels, in addition to unique rim and base fragments, reveal that the Tortugas ship was carrying a minimum of 60 tin-glazed tablewares when it sank: 35 dishes, 11 bowls, 4 cups, 5 jugs, and 5 juglets. Unglazed coarse redwares represent 11.6 percent of the tableware assemblage and glazed coarse redwares represent 6 percent (see fig. 22).

Painted across the rims of the Blue-on-Blue Seville maiolica (fig. 17) are ten different motifs, primarily schematized swirling floral variants. The interior base medallions feature eleven decorative forms: stars, fruit, and, most commonly, six variants of floral motifs with radiating petals. The same decorative scheme appears on shallow bowl bases. Comparable maiolica has been excavated from the Atocha, farther afield in the Convento de San Francisco in the Dominican Republic and in Seville itself.[7] The rim decoration seems to have been inspired by the Chinese ceramic lotus flower motif.

The Blue-on-White Talavera dishes were decorated in imitation of Chinese blue-on-white Wanli porcelain with vertical diaper registers and classical base motifs (fig. 18). This class displays the most sophisticated and well-rendered decoration on thematically disparate base medallion schemes, including a bird sitting on a rock, garden landscapes, a playful dog, and a radiating floral motif. Three additional dishes bear heraldic or religious motifs, including two crossed keys surmounted by a cross, and two dish fragments inscribed with the letters CAR and MO, perhaps parts of ecclesiastical names (Carmel? Monasterio?).

The purity of the White Seville wares imitates the finish of Chinese kraak porcelain. The wreck’s two variants are a deep bowl, whose sole decoration is two sets of three short vertical dark blue lines on the rim, and an incomplete small cup, taza (see fig. 20).

The thick-bodied Columbia Plain dishes (fig. 19) and bowls are the best-preserved vessel forms from the Tortugas shipwreck. The dishes have an approximate diameter of 7 3/4 inches, and the bowls are about 5 1/8 inches. The distribution of this ceramic type is the most recognizable colonial ware of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and follows the routes of the Seville-based fleets. The cheap ware has been hypothesized to be the standardized “official issue” of the Casa de la Contratación.[8] It was also the most widely used tableware in the Americas, representing, for instance, more than 80 percent of all sixteenth-century maiolica at Puerta Real in Haiti.[9]

Sturdy Columbia Plain wares were the most common tableware on the St. John’s wreck sunk off the Little Bahama Bank soon after 1554, as well as on the Emanuel Point wreck from the flota of Tristán de Luna, which was lost during a hurricane in 1559 during the first European attempt to colonize Florida.[10] The Columbia Plain ware recovered from La Trinidad Valencera, which sank in 1588, were largely unchanged morphologically.[11] The fact that this product line accounts for just 6.1 percent of the total Tortugas tablewares, however, perhaps points to weakened centralized control over the flota and the emergence of greater individualism—but at the very least changing cultural tastes—by 1622.

The tablewares are completed by a cheerful set of two-handled Andalusian Polychrome juglets, one version painted with a dark blue fruit motif on a lighter blue surface, the second with blue and yellow painted floral motifs overlying a brownish cream background (fig. 20). This form, which presumably was used to pour oil at a table, comprises 2.3 percent of the tablewares. Though well preserved, decorated linear Blue Morisco one- and two-handled jugs and mottled Blue Morisco cups represent just 3.7 percent of the Tortugas tablewares (fig. 21). Blue-on-White Seville bowls and juglets and one San Juan Polychrome juglet account for just 0.9 percent and 0.5 percent, respectively.

Fingerprinting Pottery Origins

Colonial Andalusia’s highly structured dietary provisioning customs have been denounced as “veritable economic lunacy.”[12] While severe, the accusation was made in reference to Seville’s single-mindedness when it came to expanding its revenue. On average, a typical Atlantic-bound Spanish ship carried enough wine to last 191 days and enough beans, chickpeas, and rice to sustain 500 men for 273 days.[13] In order to be as self-sufficient as possible and to avoid reliance on the uncertainties of foreign supply, holds were stocked with products made and packaged in and around Seville. Commercial competition was discouraged, and almost all foreign produce was considered contraband.[14]

To what degree do the Tortugas ship’s ceramics reflect Iberian economic tunnel vision? This question was addressed in 2011 by a chemical analysis of sampled Tortugas pottery clay bodies using ICPS to identify chemical fingerprints. ICPS investigates whether ceramics derive from the same clay source by examining atomic emissions for all the major chemical elements and a range of trace elements. This method has the advantage of straightforward calibration, consistent accuracy, precise results, and ready availability as a technique.[15] The results were compared with the chemical characteristics of Seville-produced pottery, which was examined on previous projects using ICPS and neutron activation analysis (NAA).

The representative selection from the wreck consisted of fifty-seven examples, principally olive jars, maiolica, Morisco wares, redwares (fig. 22), and colonoware cooking vessels. Powdered samples were obtained by drilling into a broken edge or inconspicuous part of a whole object using a small, solid-diameter tungsten carbide drill bit fitted into a handheld electric drill. The powders were analyzed using a standard technique for ICPS. Detailed interpretation of the analyses was carried out with multivariate statistics, which simultaneously considered the concentrations of many elements in each sample, including Principal Components Analysis (PCA) and Discriminant Analysis (DA).

The results revealed that, with a few exceptions, the clay chemistry is consistent within each ceramic type (that is, they were made from the same clays or clay mixtures, and perhaps all from the same workshop). The analyses clarified, however, that the types fall into two major chemical groups (apart from olive jar Type 1, which have a different chemistry). These groups correspond to Seville wares and Morisco wares, respectively.[16] Comparison with previous ICPS and NAA results confirms both main chemical groups are Seville products but were made of slightly different clay mixtures. This appears to be the first time this chemical distinction in the body of the two series of wares has been recognized. Substantial numbers of earlier Morisco Spanish wares, including examples found in the Caribbean, Venezuela, and at a kiln site in Seville, have been previously analyzed.[17] Support for the conclusions about the two clay mixtures also came from previous extensive studies conducted in the 1980s on raw clays from the Seville region and throughout Andalusia; clay matching the Tortugas pottery can be found in the Seville area.

The Type 1 olive jars are all of the same paste chemistry, but differ chemically from the rest of the Tortugas pottery, indicating they were unlikely to have been produced near Seville but are similar to the analysis of Dressel type 20 Roman amphoras produced in the region of Cordoba.[18]

A large proportion of the Seville wares from the Tortugas shipwreck formed one of the two major chemical groups. All of the Blue-on-Blue Seville products analyzed were very chemically similar both to each other and to the Blue-on-White Talaveran style. The Blue-on-Blue products can be difficult to identify and classify visually because they are easily confused with extremely similar, contemporaneous Italian prototypes that provided the inspiration for the Spanish versions; they are also similar to imitations from Mexico.[19] However, chemical analysis can distinguish the fabric of Italian, Spanish, and Mexican ware, and the Tortugas investigation appears to be the first in which significant numbers of Blue-on-Blue wares made in Seville were chemically analyzed. Some Blue-on-Blue were formerly attributed to production in Talavera, Spain, but published studies indicate that Talavera maiolica has distinctive differences to Seville wares.[20] None of the Tortugas pottery bears the chemical signature of Talavera, but is of Seville origin.

Also belonging to this first clay chemical group was Blue-on-White Talavera pottery. When found on New World sites, Talaveran or Talaveran-influenced maiolica can be difficult to assign to its production origin because the style was imitated in Seville.[21] However, chemical analysis makes clear that the Blue-on-White Talavera pottery from the Tortugas shipwreck was produced at Seville and not Talavera. Talaveran-style pots were also manufactured in Puebla, Mexico, but again, these products are different chemically from Seville products.

Andalusian Polychrome does not seem to have been previously analyzed, but was found to be chemically part of the Seville wares group. Not identical to the Blue-on-Blue wares but similar chemically, Type 2 globular olive jars again bear the chemical signature of Seville clays (in stark contrast to the elongated classic Type 1 variants). The high percentage of sand in these clays made them especially suitable for manufacturing heavy olive jars. The distinguishing chemical feature of the Type 2 olive jars is their relatively low alumina and lime. A matching chemical composition was found in clay from the banks of the Guadalquivir at Seville, indicating the source.

Two Seville White wares both proved to be chemically similar to the Blue-on-White Talavera pottery and Type 2 olive jars. The White wares contain more lime and alumina than the Type 2 olive jars, which could have resulted from the mixing of some “fat” clay from the Triana district with the “short” clay used for the jars.[22] The White wares are distinguished from Columbia Plain products by their fabric color and forms. While the Columbia Plain wares analyzed in this project were shown to have divergent compositions, the Seville White pair are chemically very similar and match the other Seville wares, suggesting closer control over their production and manufacture in limited numbers of workshops located in Seville itself.

Morisco wares formed the second major clay chemical group, which was higher in lime (calcium oxide) and lower in the percentage of clay-related chemical elements, indicative of a higher percentage of quartz sand temper relative to the Seville wares. Four Columbia Plain maiolica were examined and found to contain three different paste chemical compositions: one had the chemical signature of Seville; one seemingly had the signature of New World ceramics; and the other two formed part of a previously unreported group containing high levels of magnesium present as the clay mineral montmorillonite (up to about 11% magnesium oxide in the paste, compared to 2–3% in Seville pottery).

Columbia Plain was a highly popular ware and examples are associated with a kiln at Triana in Seville. However, the current study points toward production at multiple locations. The high magnesium subgroup represents a diversity of pottery types, including two blue Morisco wares, a half-dipped juglet, and some Columbia Plain. Among the extensive range of published analyses of raw clays from the Seville area, only two contained such high levels of magnesium, namely those from the villages Benacazon and Aznalcazar located about fifteen miles west of Seville, close to the Rio Guadiamar. These clay beds lie in the Aljarafe olive-producing area and suggest that these individual examples of Morisco and plain wares were produced in a previously unrecognized rural pottery.

A striking result among the Tortugas pottery is the variety of paste chemistry that contrasts strongly with the single chemical composition published for Seville pottery (for example, for imports at five sites in the Dominican Republic, one in Venezuela, and one from the Carthusian monastery at Jerez, Spain).[23] Our study has revealed the use of at least two major categories of clay: the high lime and quartz sand but lower clay percentage in the paste of Morisco wares; and the higher clay but lower lime and quartz in the more refined pastes of the Seville wares influenced by Italian potters.

Can we propose whether any of the Tortugas types were produced in the same workshop using the same clay mixture? Identity of chemistry for pastes implies the same clay mixture; subtle chemical variations, however, could indicate production in a different workshop or in divergent chronological periods within a single workshop. The case is strongest for the Blue-on-Blue Seville wares—they are sufficiently close chemically to be consistent with production in the same workshop. The Blue-on-White Talavera is slightly different and has more in common with the Seville White Wares, perhaps indicating manufacture in another workshop. The “high magnesium” group is unlike the Seville wares and a rural provenance is surmised. The olive jars were produced in altogether different workshops.

Conclusions

The ceramic repertoire from the deep-sea Tortugas shipwreck expands our knowledge of early-seventeenth-century shipboard life in Andalusia, the Americas, and as far as the Pearl Coast in eastern Venezuela. In the absence of high-status silver or pewter, pottery served as the exclusive medium for tableware on this modest merchant vessel. While adhering to Seville’s commercial control over flota supplies, the assemblages offer a more nuanced snapshot of cultural tastes in the early years of King Philip IV’s reign.

An Andalusian guest aboard the ship would have encountered familiar home comforts. Many of the tablewares are renowned from scenes of domestic still life in Seville depicted in the works of Diego Velázquez, Francisco López Caro, and Francisco de Zurburán of the 1620s and 1630s. Seville and Andalusia clearly dominated the market for ceramic tablewares on this Tierra Firme fleet vessel, but with greater regional market availability than previously appreciated.

The chemical analysis reveals that the jars filled with olive oil, wine, nuts, and other foodstuffs were produced across a wide expanse of Andalusia on the banks of the Guadalquivir in Seville (Type 2 olive jar) and northeast up the river at Cordoba (Type 1 olive jar). Such connectivity is not unexpected and a model of competitive Seville aristocrats and merchants owning rural estates upstream and closer to the city seems likely (possibly including some Church control). Kilns almost certainly adjoined fields and haciendas in the same rural productive structure developed by Rome for Baetica’s mass olive oil exports sixteen hundred years earlier than when the Tortugas ship sank.

The vast majority of the Tortugas tablewares were produced in Seville, presumably within the famous “potters quarter” of Triana, albeit seemingly in different workshops. The Blue-on-Blue Seville, Andalusian Polychrome, Seville White, and Blue-on-White Talavera wares were all local to Seville and not—as is often supposed for the Blue-on-White—imports from Talavera. This result fits historical references to potters (including a Moor) turning out “Talavera glazed ware” in Triana and near the Puerta de Goles between 1587 and 1615. These must have been the platos de Talavera contrahechos en Sevilla (plates of Talavera imitated in Seville) and platos pintados contrahechos de Talavera (painted plates of Talavera in imitation of Talavera) referred to in Spain’s Tasa de Precios price regulations of October 12, 1627.[24]

Two types of Tortugas tableware diverge from the picture of Seville’s monopoly. The four Columbia Plain maiolica contained three different chemical fingerprints, indicative of multiple production sources in Seville and in a rural Andalusian context fifteen miles west of Seville. The blue Morisco wares and half-dipped juglet adhere to the same “high magnesium” group, which represents a hitherto unidentified major pottery production site.

Four other product lines break the trend of Andalusian monopolization. Completely unexpectedly, one of the Columbia Plain samples seems to match New World ceramic chemical signatures. Combined with evidence of bowl manufacture at Mata da Machada, Lisbon, circa 1550–1570, and possibly in dish form in Mexico in the first half of the sixteenth century, far wider long-distance colonial imitation must now be considered for this ware.[25] This evidence may explain its dominance among maiolica in colonial assemblages from Armada ships lost off Ireland to the New World. To these outliers can be added the identification, based on visual examination, of one 11 3/8-inch-tall jug with a trefoil pouring spout and a single, bifurcated strap handle as originating in Aveiro, Portugal, and one San Juan polychrome maiolica juglet from the New World.[26]

The single major exception to the dominant Andalusian regional focus among the Tortugas ceramics—the kitchen vessels—are all highly coarse utilitarian colonoware of New World manufacture (fig. 23). Recovered were 47 rims, 11 bases, and 1 handle, plus another 220 unattributable body fragments. Traces of soot and charring are common on these fragments. The same colonoware forms were used on the Atocha. Why should the Tierra Firme fleet have stuck so closely to home products for its tablewares but have selected native-made American products for its cooking vessels?

Spanish ships departing from Andalusia had access to the finest Iberian ceramics in circulation. Not only does the Tortugas colonoware differ dramatically from these products, it also seems not to replicate European pot forms.[27] One explanation for this anomaly could be the presence of slaves, most probably African at this time, who chose to use familiar tribal pottery to cook the crew’s food. Confined below decks, this crude earthenware would not have been conspicuous on the ship’s dining table.

Alternatively, if the cooking pots had broken during the outward-bound voyage, the crew could have picked up these wares as replacements, which were produced as far afield as Venezuela and Chesapeake. The samples of Tortugas colonoware analyzed by ICPS are characterized chemically by very high sodium content—typical of Valley of Mexico pottery, which may tentatively be identified as a source. If correct, it is tempting to propose that these wares were purchased at Havana, the regional collecting point for colonial re-exports where returning Spanish ships converged for supplies and into the port of which local regional trade could have easily shipped Mexican products.[28]

The Tortugas shipwreck’s ceramic assemblage reinforces the image of a mercantile monopoly centered on Seville for the 1622 Tierra Firme fleet and, ultimately, on its privileged maritime status in the shadows of the Casa de la Contratación, which exerted rather than politically enforced an enormous economic gravitational pull. The pottery is not without its quirks, notably the reliance on indigenously produced colonoware.

The overriding degree of self-reliance within this maritime context was not shared by other contemporary superpowers. At the plantation site of Martin’s Hundred in Virginia, for example, the English merrily imported Dutch, French, Rhenish, and even Spanish pottery for daily use without eroding their national values.[29] Non-Spanish wrecks exhibit the same expansive cosmopolitan worldview. For example, the Portuguese Nossa Senhora dos Martires, which was wrecked in the River Tagus, Lisbon, in 1606, used stoneware jars from southern China to transport foodstuffs. And by far the largest collection of ceramics recovered from the Dutch East Indiaman Batavia (wrecked off western Australia in 1629) were Rhenish salt-glazed stonewares.[30]

Madrid’s fixation in the first quarter of the seventeenth century with single-source products from core locations (silver from Potosi, pearls from Cumana, gold from Colombia) would eventually prove to be its Achilles’ heel and one cause of Spain’s economic collapse. The Tortugas wreck’s overall preoccupation with hometown pottery serves as a microcosm of this unsustainable inflexibility in the waning years of the Golden Age of Spain.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors sincerely thank Greg Stemm, Mark Gordon, Laura Barton, and John Oppermann of Odyssey Marine Exploration for supporting the publication of the Tortugas shipwreck. Chad Morris prepared the ICPS samples for analysis and Alan Bosel produced photographic records of all the ceramics (both of Odyssey). Mark Sullivan and Mark Musset, also of Odyssey, patiently assisted with Spanish archival translations and map production. The project would not have been possible without the pioneering technology developed by John Astley, the diligence of David Moore as field archaeologist, and the post-excavation research of Jenette Flow.

Mitchell W. Marken, Pottery from Spanish Shipwrecks, 1500–1800 (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1994).

John M. Goggin, The Spanish Olive Jar: An Introductory Study, Yale University Publications in Anthropology 62 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1960).

Based on George Avery’s analysis of the Tortugas wreck collection; see George Avery, Pots as Packaging: The Spanish Olive Jar and Andalusian Transatlantic Commercial Activity, 16th–18th Centuries, Ph.D. diss., University of Florida, 1997, pp. 103–4, 106, fig. 15.

Ibid., p. 123.

Alfonso Pleguezuelo-Hernandez, “Seville Coarsewares, 1350–1650: A Preliminary Typological Survey,” Medieval Ceramics 17 (1993): 39–50.

In terms of cargo, ongoing research points toward an organic cargo transported back to Spain on the Tortugas ship, most likely Venezuelan tobacco picked up at Cumana when the ship purchased pearls.

John M. Goggin, Spanish Majolica in the New World: Types of the Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries, Yale University Publications in Anthropology 72 (New Haven, Conn.: Department of Anthropology, Yale University, 1968), p. 137, fig. 12b; Florence C. Lister and Robert H. Lister, Andalusian Ceramics in Spain and New Spain: A Cultural Register from the Third Century b.c. to 1700 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1987), p. 159, fig. 102. The Atocha pottery is illustrated in Mel Fisher’s Historic Shipwreck Research Database, available online at www.historicshipwrecks.com (accessed May 5, 2012).

Colin J. M. Martin, “Spanish Armada Pottery,” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology and Underwater Exploration 8, no. 4 (1979): 286.

Charles R. Ewen, From Spaniard to Creole: The Archaeology of Cultural Formation at Puerto Real, Haiti (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1991), p. 62.

Martin, “Spanish Armada Pottery,” pp. 284–86; Marken, Pottery from Spanish Shipwrecks, pp. 154, 156–57, figs. 5.9, 5.10, pl. 18; Corey Malcom, St. John’s Bahamas Shipwreck Project. Interim Report I: The Excavation and Artifacts 1991–1995 (Key West, Fla.: Mel Fisher Maritime Heritage Society, 1996); Carrie Williams, “Analysis of Tin-glazed Ceramics from the Emanuel Point Ship Second Campaign,” in Roger C. Smith, John R. Bratten, J. Cozzi and Keith Plaskett, The Emanuel Point Ship: Archaeological Investigations, 1997–1998, Report of Investigations 68 (Pensacola: Archaeology Institute, University of West Florida, 1998), p. 141.

Marken, Pottery from Spanish Shipwrecks, pp. 154, 156–57, figs. 5.9, 5.10, pl. 18; Martin, “Spanish Armada Pottery,” pp. 284–86.

Perre Chaunu and Hugette Chaunu, “The Atlantic Economy and the World Economy,” in Peter Earle, ed., Essays in European Economic History, 1500–1800 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974), p. 120.

Douglas R. Egerton, Alison Games, Jane G. Landers, Kris Lane, and Donald R. Wright, The Atlantic World: A History, 1400–1888 (Wheeling, Ill.: Harlan, Davidson, 2007), p. 219.

David C. Goodman, Spanish Naval Power, 1589–1665: Reconstruction and Defeat (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), pp. 138–39.

For a typical application, see Michael J. Hughes, “Inductively Coupled Plasma Analysis of Tin-glazed Tiles and Vessels Produced at Several Centres in London,” in Kieron Tyler, Ian M. Betts, and Roy Stephenson, London’s Delftware Industry, MoLAS Monograph 40 (London: Museum of London Archaeology Service, 2008), pp. 120–31.

As defined in Alexjandra Gutiérrez, Mediterranean Pottery in Wessex Households (13th to 17th Centuries), BAR British Series 306 (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2000), p. 44. Seville wares are maiolica varieties produced in Spain in response to Italian influence. It is important to recognize that the descriptive term Morisco wares common in Spanish ceramic studies is technically incorrect when applied to the Tortugas shipwrecks pottery because Seville’s Morisco Muslim community was expelled in 1610, more than a decade before the ship’s voyage in 1622: Ruth Pike, Aristocrats and Traders: Sevillian Society in the Sixteenth Century (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1972), pp. 163, 168. Moriscos thus cannot have crafted these wares, even if they originally inspired some styles.

Jacqueline S. Olin, Garman Harbottle, and Edward D. Sayre, “Elemental Composition of Spanish and Spanish-Colonial Majolica Ceramics in the Identification of Provenience,” in Giles F. Carter, ed., Archaeological Chemistry—II, Advances in Chemistry Series 171 (Washington, D.C.: American Chemical Society, 1978), pp. 200–229; James E. Myers, Francis de Amores Carredan, Jacqueline S. Olin, and Alfred Pleguezuelo Hernandez, “Compositional Identification of Seville Maiolica at Overseas Sites,” Historical Archaeology 26, no. 1 (1992): 131–47.

For Dressel 20 amphoras, see Neil Cunningham Dobson, Michael Decker, and Sean Kingsley, A Cargo of Baetican Dressel 20 Olive Oil Amphoras in the Western Alboran Sea (Site ASDS-6), OME Papers (Tampa, Fla.: Marine Exploration, forthcoming).

Kathleen A. Deagan, Artifacts of the Spanish Colonies of Florida and the Caribbean, 1500–1800, Volume 1: Ceramics, Glassware, and Beads (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987), p. 61.

A. Ray, Spanish Pottery 1248–1898 (London: V&A Publications, 2000), pp. 172, 180.

Deagan, Artifacts of the Spanish Colonies, pp. 64–65.

Fat (long) clay has a high plasticity and strength (high percentage of clay minerals); short (lean) clay has a lower plasticity and strength (and lower percentage of clay minerals); see Frank Hamer and Janet Hamer, The Potter’s Dictionary, 5th ed. (London: A. & C. Black, 2004).

Olin et al., “Elemental Composition of Spanish and Spanish-Colonial Majolica.”

Anthony Ray, Spanish Pottery, 1248–1898 (London: V & A Publications, 2000), p. 180.

Tânia Manuel Casimiro, Portuguese Faience in England and Ireland, BAR International Series 2301 (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2011), p. 144, fig. 71; Florence C. Lister and Robert H. Lister, “Maiolica in Colonial Spanish America,” Historical Archaeology 8 (1974): 24, fig. 3a.

Beverly Straube, personal communication, November 16, 2011; Tânia Manuel Casimiro, personal communication, January 23, 2012; Marken, Pottery from Spanish Shipwrecks, p. 233, pl. 40.

Kathleen Deagan, “The Archaeology of the Spanish Contact Period in the Caribbean,” in William F. Keegan, ed., Earliest Hispanic / Native American Interactions in the Caribbean (New York: Garland Publishing, 1991), pp. 215, 356.

For the role of Havana in flota supplies, see Alejandro De la Fuente, Havana and the Atlantic in the Sixteenth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008)

Ivor Noël Hume and Audrey Noël Hume, The Archaeology of Martin’s Hundred: Part II, Artifact Catalog (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology; Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2001), pp. 239, 243, 275–78, 329, 337.

For the Nossa Senhora dos Martires, see Sara R. Brigadier, The Artifact Assemblage from the Pepper Wreck: An Early Seventeenth Century Portuguese East-Indiaman that Wrecked in the Tagus River, master’s thesis, Texas A&M University, 2002, pp. 108–16. For the Batavia, see http://202.14.152.30/collections/maritime/march/artefacts/Batarts.html (accessed October 26, 2012).